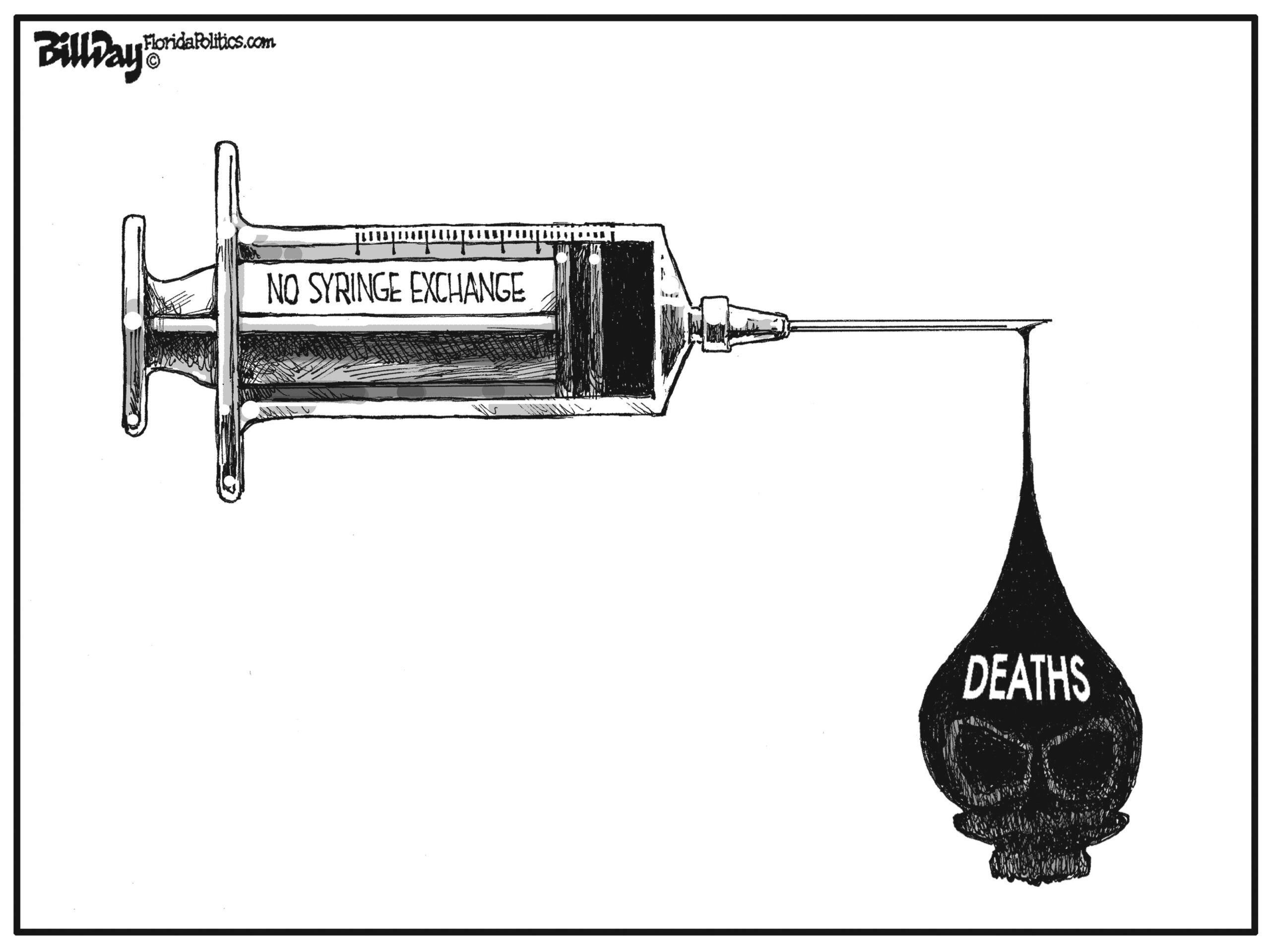

Only Gov. Justice’s veto stands between the people and SB 334, regarding needle exchange programs, and the deaths it may cause.

We’re not being melodramatic, though it may sound like it.

Though the language of the bill is mild enough, it includes several mandates that could kill or severely restrict needle exchange programs (also called syringe services programs, or SSPs), such as requiring a letter of support from the city and county that can be rescinded at any time.

The bill also requires any SSP to be part of a licensed harm reduction program. On the surface, this seems to make sense: Harm reduction programs offer the resources that help people reach sobriety and stay healthy, such as vaccinations, virus testing and social services. But SSPs should still be allowed to operate in the absence of a harm reduction program, because SSPs take care of the immediate threat of disease spread through using shared or dirty needles for intravenous drug use.

When Kanawha County shut down its health department-run needle exchange in 2018, HIV and Hepatitis C cases skyrocketed. The county now has a CDC-recognized HIV outbreak, largely caused by drug use. Last year, Kanawha County recorded 35 HIV cases; only one less than New York City reported the year before.

A nonprofit organization, Solutions Oriented Addiction Response or SOAR, tried to step in to fill the void last year, providing needle exchanges and HIV testing. The city shut it down, temporarily, because it was not licensed.

Charleston points to WV Health Right, its licensed harm reduction program, as the reason it has no need for intervention by organizations like SOAR. But according to data from the DHHR and compiled by Mountain State Spotlight, WV Health Right has the state’s third lowest rate of syringe distribution despite serving one of West Virginia’s most populous counties. And we can see how the absence of clean syringes has fueled the HIV outbreak.

One of the reasons WV Health Right gives out so few clean injection supplies is because it has a strictly enforced one-for-one policy, where intravenous drug users are only given as many clean syringes as used syringes they return. Milan Puskar Health Right here in Morgantown, on the other hand, distributes the most syringes — and Mon County hasn’t had more than five drug-use-related HIV cases in any of the last five years. However, the one-for-one policy will become a statewide mandate if SB 334 becomes law.

The logic seems to be that returning used needles to the SSP in exchange for new syringes prevents needle litter in the community. But the opposite is true. According to the CDC, the National HIV Behavioral Surveillance System “found that the more syringes SSPs distributed per the number of people who inject drugs in a geographic region, the more likely the people who inject drugs in that region were to dispose of used syringes safely.”

According to the Harm Reduction Coalition, the most effective SSPs are those with low-barrier access. That means no one-for-one exchanges — which deters people who don’t have a syringe to exchange — from getting a clean one, and no ID requirements — which would also become required in SB 334 is signed into law — because being required to give personal information tends to make people wary of using the program.

SB 334, if signed into law, can literally kill people. The restrictions on the programs will make it harder for intravenous drug users to access the equipment they need to keep themselves and the community safe. SSPs are a key step toward getting resources and services for sobriety to the people who need them most. And if the needle exchange program isn’t accessible — and SB 334’s mandates would make it far less accessible — we face potential blood-borne viral outbreaks throughout the state, and the loss of life associated with them.

Gov. Justice must veto SB 334. Otherwise, the consequences will be deadly.