Noah Smith, Dave Truban and Jeff Kittle are three guys you wouldn’t imagine having a connection. Although the trio lived near each other over the last two years, only one other major thing brings this group of friends together: Their passion for upland bird hunting, specifically ruffed grouse.

But more on Kittle and Truban later – first we dive into how a 23-year-old is thriving as a grouse hunter.

Smith, a forestry student at West Virginia University, is in his final year of undergrad within the Davis College. A native of North Carolina, Smith moved to Morgantown after two years of schooling in his home state, and it’s at WVU where he’ll finish his studies in May. While he’s been here, though, his longstanding love of chasing upland birds never ceased.

“I have [hunted] extensively in the [Monongahela] National Forest from the southern part of the state to the north, and in Monongalia and Preston counties,” Smith said.

When told he probably has about the same amount of experience as local hunters his age – “I don’t know about that,” he said laughing. “I’ve spent a lot of time in the woods and behind a dog for sure.” – he handles it with a gracious, humble southern charm.

Going on 7 years hunting upland birds, Smith has seen a steady decline in ruffed grouse in his home state. North Carolina is facing a similar situation that West Virginia and the rest of middle to southern Appalachia are, which is one of the main reasons Smith has decided to pursue forestry.

“The North Carolina Wildlife Resources Commission has been documenting the decline for the last 30 years. So, they’ve got a lot of really great data that shows the decline in ruffed grouse,” he said. “Some years are better than others. Some years for West Nile are really bad if you have a warm, wet spring, but once you get above that elevation threshold the birds can make a comeback. Talking to people from West Virginia and looking at the marginal habitat in western North Carolina, at lower elevations you see a disappearance of the bird. But I’m hopeful. I’ve been involved in the Nantahala and Pisgah National Forest management plan revision for the last six years, and I tell people, ‘Rather to have fought and lost than not to have fought at all.’”

And although West Virginia Division of Natural Resources Wildlife Manager Rob Tallman noted that not everyone knows the set-in-stone elevation that West Nile stops breeding, to Smith it’s around the mystical 2,000 feet.

“Depending on microclimate, the magic number for everybody is about 2,000 feet because you have a climate change and forest type change at that elevation – I’ve seen them as low as 1,200 feet in North Carolina, but mostly when you include the latitudinal difference, 2,000 feet is a good rule of thumb,” he said.

Connections, connections

For a young guy in his closing year of undergrad, you’d imagine he would want to get time away from studies as much as possible. But before you can even finish that thought or imagine all of the things a WVU senior could have gotten into in Morgantown, Smith has rather spent his free time networking with high-ranking members of conservation agencies.

In mid-February, Smith met with members of the WVDNR – Director Stephen McDaniel and State Wildlife Chief Paul Johansen – and the Ruffed Grouse Society – president Ben Jones and then-biologist Linda Ordiway – as well as Pennsylvania Game Commission biologist Lisa Williams and others.

“It was a presentation on West Nile Virus and the susceptibility of grouse. The main takeaway was installing quality habitat at higher elevations, which for West Virginia means public land in the Mon National Forest. Of course, there’s environmental litigation that goes along with habitat and active forest management which is the main obstacle they face right now. Plus the poor timber market right now due to the tariffs in the trade war with China and the export market being virtually nonexistent right now.”

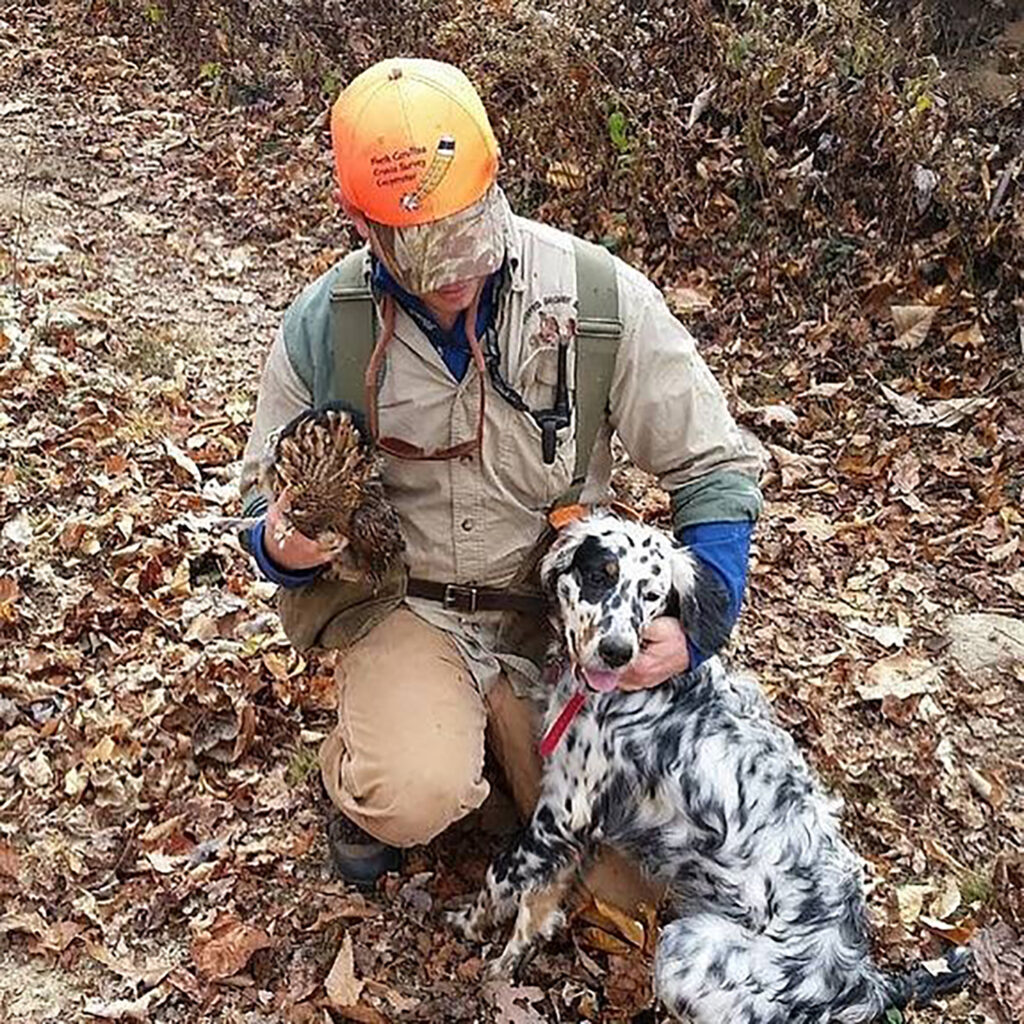

And it’s through connections that Smith met Kittle, a resident of Grafton. Kittle primarily hunts in the Elkins area of the National Forest – a perfect spot for the two to meet up and set loose their dogs. Kittle owns Brittany spaniels, while Smith has a Llewellin Setter named Jeb. While Smith is close to closing in on a decade of experience, Kittle has been hunting since he was old enough to carry a shotgun, roughly 40 years ago.

“Jeff and I hunt together, he’s a sharp fella,” Smith said. “You can tell a difference when there is habitat at those higher elevations. I’ve had double-digit days in West Virginia. Jeff and I had a day one time [when] we had 43 woodcock and grouse flushes.”

Kittle hunts from Canaan Valley south through Cheat Mountain and Seneca State Forest, down through the spine of the Appalachians – what he refers to as “the hub.” But that’s the bird epicenter of West Virginia, the hub of the United States is the Lake States and Kittle is familiar with that as well. He also knows how their model can help the Mountain State.

“I hunt Michigan in the fall, and when you go [there] you see a lot of timber cutting, especially in their aspens, on a large scale,” Kittle said. “That’s why you see a lot of grouse and woodcock [when you go there]. We’ll flush over 100 woodcock a day, it’s crazy. And they make habitat consistently, and that’s been one of the things I’ve been frustrated with on the [Monongahela] National Forest. They get so much resistance to doing any kind of habitat work, and it continues to fall behind the pace it needs to be on to not only benefit grouse but other small game and deer, too.”

Fight fire with fire?

Kittle and Smith both agree that, even though there’s plenty of success to be had hunting grouse in the mountains, there are also environmental groups trying to stop them from doing so by tying up the forest restoration agencies in court.

“It’s the environmental groups, specifically I’d say the Sierra Club,” Kittle said. “Beyond that, I don’t know of other specific ones. Sierra Club is the one I’ve heard quite a few times. It’s always an environmental group that thinks mature trees are the best way to go, even if they’d look at the data and were concerned about climate change they’d see that a young, vibrant forest is better than scrubbing carbon from the environment than old, mature trees are. [And] the young trees are growing back pretty quick.”

Though not casting a shadow on the severity of environmental groups’ interference with habitat restoration, Kittle was quick to revert to his lighthearted, joking attitude.

“I think they use endangered species against any environmental work. The Cheat Mountain salamander is one [example]. I’ve talked to a young woman sampling the Cheat Mountain Salamander a few years ago, and I couldn’t help but ask what she was doing – she was in [an area] where deer and grouse [have been taking a hit]. I told her, ‘If you guys don’t figure this stuff out soon, I’m going to be eating those salamanders soon,’ ” he said laughing.

It’s not just in West Virginia. Multiple groups are doing this across the country, and Smith notes it’s particularly detrimental in North Carolina.

“We’ve got several groups that are going to love the forest to death,” Smith said. “After having conversations with some of those people, they seem completely OK with a whole suite of species disappearing because it means active forest management isn’t happening. But with those groups, [in response] you see a lot of pushback from science-based organizations like the National Wild Turkey Federation, Quality Deer Management [and more].”

And this is where Truban, the President – or as he put it the “ring leader” – of the north central West Virginia chapter of RGS, comes in. He, too, sees certain environmental groups as a danger to wildlife as a whole, not just ruffed grouse. But while the science-based groups that Smith noted are trying to educate those on the opposing side, Truban believes it would be better to fight fire with fire, or, in this case, lawsuits with lawsuits.

“It’s not a matter of educating them, they’re educated people,” Truban said. “That’s like RGS, NWTF and conservation groups that are out there wanting to spend money and get work done so we hire biologists. But instead of hiring biologists, we need to hire lawyers, that’s what it’s going to take. They don’t care if there’s any wildlife there or not. The groups that disappoint me are the bird groups. They should be singing the same song as RGS, but they just sit there and you can’t get a response out of them.”

During his explanation of lawsuits restoration agencies have dealt with, he brought up the Big Rock timber project that was slated to take place in the southwestern range of the Monongahela National Forest. Big Rock was a 2,400-acre logging project slated to take place in the Gauley Ranger District, but after pressure from Friends of Blackwater the U.S. Forest Service canceled it. According to a Center of Biological Diversity lawyer, Jason Totoiu, “Building new logging roads and clearcutting trees on extremely steep slopes would have been disastrous for wildlife, including the beautiful candy darter.”

The candy darter is a small, native fish to the Kanawha River Basin of Virginia and West Virginia, and in 2010 the CBD and West Virginia Highlands Conservancy petitioned to add the fish to the endangered species list. Once it wasn’t added, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service was sued to have it added in 2015 and was finally put on the ESL in 2018.

But that’s just one example of many in an everlasting fight. To Truban, he believes that some groups are fighting the fight only for the payout, not truly in the spirit of conservation.

“They can call themselves environmental groups all they want. They use the Endangered Species Act as [an] unlimited license to interfere with no consequences,” he said. “Law firms have figured out how to make a fortune by suing the federal government.

“Their only concern is stopping someone from cutting their trees. They’ll say there’s plenty of young forest on [private lands]. And when you look at the Mon National Forest, there are 1 million acres and less than 1/3 of it that you can do anything on anyway. When you take the backcountry, wilderness, salamander, bat and all the other areas that you can’t do work on, they don’t want to give us that [available land]. I heard one of them say one time that they didn’t care if there was a trout in a stream or not, as long as it isn’t orange they were OK with that.”

‘Rather to have fought and lost than not to have fought at all’

Truban is quick to note that this all didn’t come out of thin air. It wasn’t a concept born from fake news or the brain of a mad scientist in some subterranean lab. This is the aftereffect of a strange time from the 1970s through the 1980s that saw the USFS cutting more than needed plus an agreement between hunters and the WVDNR.

“Back in the 1970s, the forest service got carried away. They were clear-cutting the shit out of everything. And that’s when we were trying to grow turkey numbers in the state, so the thought was, ‘If we keep cutting [at the same rate], we’re going to lose all of our oak and roosting trees, and that will keep the turkeys from growing,” he said. “The DNR and the sportsmen bought into and supported 6.2 management areas. You’re supposed to do habitat work in there, but you can’t use a commercial logger to go in and cut. It’s not a wilderness area where you can’t use anything mechanized – you could still use chainsaws – so it sounded like a good idea at the time, but what we didn’t realize was that it was taking more land out of active management. That’s how we got to where we are today.”

And with that, there are now groups who think any type of active management is bad. Luckily for the WVDNR, most projects in the National Forest are maintained at a steady pace and are scheduled to last through 2025 as long as funding holds up. That’s also good news for hunters, new and old, and with the older population aging out of the sport it’s time for a new group to carry the torch.

“I want to stress for people to get involved,” Smith said. “If we’re lackadaisical about this we’ll lose it. We’re one generation away from [hunters and hunting] all together. There’s hardly any young guys or girls that are involved in upland bird hunting. It’s not just grouse, it’s quail hunting culture in the deep south, [too]. You’re blessed with places to hunt in West Virginia. The culture is still here, so find somebody that knows what they’re doing that’s willing to take you out and get involved with them. It’s so easy to get tied up on social media asking someone where to go. People are more responsive if you say, ‘Hey I want to learn,’ and you’re sincere about it. It gets a lot of people upset if you want to go, kill one bird and post it on social media. Show that you’re dedicated, and if you’re a grouse hunter you need to be a conservationist also – one goes with the other, easily.

“Just give it a try. It’s esthetically pleasing; It’s hiking in the mountains; it’s dogs; it’s shotguns. What’s not to like about it? It’s changed my life in a better way. Rather to have fought and lost than not to have fought at all.”

To read more

This story is part 3 in an ongoing series concerning the disappearance of ruffed grouse in West Virginia. Each story so far in the series can be found above and the full series will be released as one, long-form story once finished. Andrew can be reached on Twitter @ASPellman_DPost