MORGANTOWN, W.Va. – Chances are if you live or have ever lived in Morgantown you’ve walked along the Mon River Rail-Trail. Whether you were relaxing below the WVU Arboretum, taking in Hazel Ruby McQuain Park or moving from Morgantown Brewing Company to Mountain State Brewing Company, the Mon River Rail-Trail is a community gem that tends to be overlooked.

Except, when it matters most, it isn’t. The 29-mile Mon River-Caperton trail system, which runs from the West Virginia-Pennsylvania state line to Prickett’s Fort State Park, and the 19-mile Deckers Creek Trail which runs from Hazel Ruby McQuain Park to Morgan Mine Road in Preston County, was inducted into the Rails-to-Trails Conservancy Hall of Fame last week following a national vote. The honor makes it the 34th inductee in the history of RTC. Even better, it beat rail-trail systems in Pittsburgh, Milwaukee and Illinois – much bigger population centers than Morgantown – by a landslide.

“That’s pretty significant,” RTC’s Director of Trail Development Kelly Pack said. “That is a testament to the amazing grassroots support that the trail has. And Wisconsin and Pennsylvania are two of the states with the most RTC members.”

“The Mon River Rail-Trails are an entrance into the beauty of the Appalachian Mountains and all the bounty of wildflowers, wildlife, waterfalls, and birds, that comes with it,” Ella Belling, executive director of the Mon River Trails Conservancy, said. “These rail-trails also show off our community spirit and unique character. The beauty of local artists grace the rail-trails, the talents of local musicians can be heard at two trailside outdoor amphitheaters, community festivals, and in our trailside bars, and the flavors of our town can be tasted at many trailside restaurants and breweries in Morgantown and Star City. The Mon River Rail-Trails are a West Virginia gem that welcome, energize and restore the heart and mind of those who choose a rail-trail adventure.

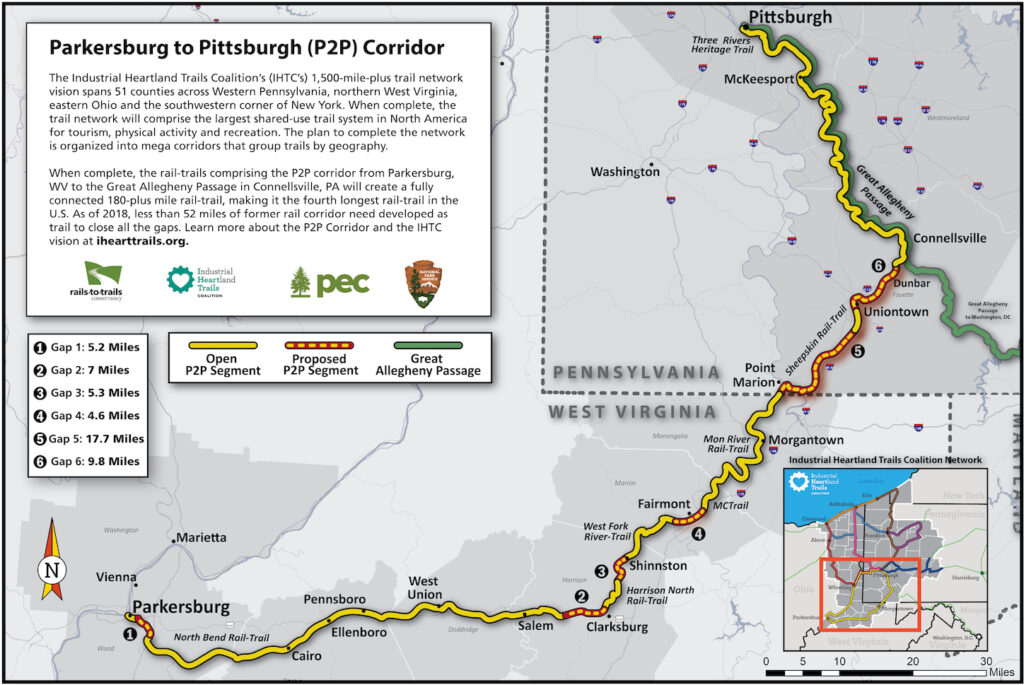

While a clear victory for the Mountain State, the Mon River Rail-Trail system is only part of a large network of trails around the state. It is, however, the model of success for those other trails and is the center point in the Parkersburg-to-Pittsburgh project that Pack has been heading, which would expand the tourism drive in West Virginia. And it wouldn’t just get folks from the Steel City but could draw people traveling from Washington D.C. on the Great Allegheny Passage Trail, a 150-mile stretch of rail-trail that crosses through the Cumberland Narrows, Eastern Continental Divide, Ohiopyle State Park and more.

The link to the community Belling noted is what the Mon River system can hang its figurative hat on. Construction began in 1998 after the Mon River Trails Conservancy was formed in 1991. There were skeptics at first, but it didn’t take long for it to begin driving economic development, provide transportation corridors for those who work along the trail and spur activists to clean up and protect the ecosystems that encompass the trails, such as Deckers Creek. Along the Mon River Trail, the brightest example is the revitalization of the Wharf District. Once a barren strip of riverbank full of abandoned buildings and other eye-sores, it’s now a vibrant area with restaurants, offices and hotels.

“The early vision was to transform the Morgantown riverfront from abandoned warehouses and industrial wasteland into a valued community asset and re-establish community life with a mix of residential and businesses,” Belling said. “That vision continues today with more neighborhood links to the rail-trail system in the works, and more trail art, more trailside music, and more community causes being funded with runs, walks, and cycling events. Though known as a rail-trail hub in the university town of Morgantown, the rail-trails route through a mix of urban amenities, remote outdoor beauty of forests and creeks, and small rural communities in three counties of North-central West Virginia. At the earliest stages, this dedicated, founding group envisioned changes to the community health and the health and wellness of its residents being greatly improved with a 50-mile rail-trail. Even then, they had the dream of seeing hundreds of miles of connected trail as negotiations with CSX were happening on nearby corridors in WV and Pennsylvania.”

Belling herself has benefited from the trail system. After almost 30 years with the conservancy, she can say it’s a job she loves.

“I love to hear peoples’ stories that are associated with their adventures on the trail,” she said. “There is a lot of patience and setbacks that have to be connected to my job, but I go out, bike and hike, enjoy nature and enjoy going into our trail-side shops. It’s just been a wonderful community asset for someone who lives in Morgantown. It’s an amazing backyard asset to go on a 50-mile trail.”

A statewide and national impact

While at the face of it the Mon River Rail-Trail is hyperlocal, the Hall of Fame recognition will have greater impacts on the state and nation.

“We’ve been working on rail trails for 35 years here in West Virginia and we have some great successes then periods of relatively little activity,” said Kent Spellman, a long-time proponent of state rail-trails and the former director of the West Virginia Community Development Hub. “We are entering, in my opinion, a [time of] real opportunity to grow trail systems across West Virginia – not just rail-trail systems, but other types of trails as well. And what this recognition provides the ability for other parts of the country to see West Virginia as a trail state in a way a lot of people don’t understand and aren’t aware of right now.

“We have the potential to be [a] trail Mecca, certainly of the eastern United States, and we have not leveraged that opportunity as well as we could. This award brings recognition from others outside of West Virginia, but more importantly, it will motivate West Virginians in other parts of the state to say to themselves, ‘Well, if they can do it in Mon County, why can’t we do it here?’ ”

Spellman also notes that, in shifting communities, the local trail is becoming the new Main Street. Instead of conversations at the Post Office, he says, folks are stopping to chat on their walk down the trail.

“People don’t walk on Main Street much anymore but they do walk on rail-trails,” he said. “I’ve seen this rail-trail we work on here in Harrison County – there are all sorts of people who stop regularly and have conversations with people they meet on the trail.”

Access to outdoor recreation is also becoming a mandatory amenity for people moving to a new area. Whether it’s access to rock climbing, kayaking, game lands for hunting, streams for fishing or trail systems for hiking and biking, West Virginia is at the front of the pack to provide this for incoming residents or in-state transplants.

“Access to trails makes a community more attractive to families. So it can be a community and economy builder because of that,” Spellman said.

“I think the [Hall of Fame] trails represent some of the most iconic and beautiful trails in our country, and they do exactly what Kent just described,” Pack added. “Nationally, there are 2,200 rail-trails now across the country and more than 25,000 miles. I was starting at WVU when [the Mon River Rail-Trail] was under construction and I saw how it transformed the whole city. And that transformative power is what we see and want to recognize in the trails we lift up with this honor.”

As a leader of economic development for decades, Spellman got this start as Ritchie County’s Economic Development Director. There he learned both sides of development around trails involving Cairo, the epicenter of the early 1900s Ritchie County oil boom, a town that is now, unfortunately, a husk of its former glory.

Cairo, which borders North Bend State Park, is an access point for those wanting to explore that system of rail-trails. Although the retreat of oil companies saw a decline in the town’s prosperity, the locals were resilient and maintained the small-town vibrance for many decades after. Up until the early 2000s, there was a popular ice cream shop, bike store and more, which catered to State Park visitors and locals alike, but as time took its toll, the town never pushed forward. Spellman saw this when he led the EDA, recruiting eight businesses to the small town to try and give it the boost it needed.

But things didn’t go well. Simply, the trail wasn’t being maintained.

“There’s a chicken-and-egg tension with trails,” Spellman said. “If you have a trail, no matter how beautiful it is, and there aren’t amenities along that trail to provide trail users their needs, then they aren’t going to have the greatest experience. On the other hand, if you put in a bunch of businesses and the trail isn’t adequately maintained and promoted and connected, those businesses are going to dry up on the vine. That’s what happened to Cairo. We didn’t maintain the trail well enough, we didn’t invest in big areas that were terrible to ride on, and we know that the longer the trail is the more outsiders it’s going to attract because it becomes a destination for longer journeys.”

With that experience under his belt, he and Pack have been working on the Parkersburg-to-Pittsburgh Corridor project. This is where all the strings begin to connect, and this is where the Hall of Fame recognition becomes incredibly important.

“I think the recognition will raise the importance of completing P2P,” Spellman said. “We hope that will mean our legislators and our governor will put more pressure on CSX to close those gaps. We hope it will cause them to put pressure on DOH to ramp up its capacity to administer the grant programs that fund most of the trail work in West Virginia. That recognition could motivate a lot of good change that we’ve been working on for a long time.”

And should the P2P get completed? Those areas like Cairo would finally benefit from well-maintained sections.

“One of the really cool things about the Mon River Trail system that differentiates it from others in the Hall of Fame is that it’s starting to demonstrate trails as systems and networks – really, what is the next phase of rail-trails in America,” Pack said. “[Rail-trails] began as a movement where people rallied around a single corridor, but Mon River is a system with the potential to connect further south through Fairmont and Clarksburg into Parkersburg, and further north into Pittsburgh to create the Pittsburgh-to-Parkersburg Corridor. I think that the recognition state-wide is so important because it shines a light on West Virginia and all the good trail development and programming, as well as some of the things that local businesses do to make it a tourist attraction. Personally, it’s really exciting because it’s my favorite trail. It introduced me to this whole amazing world and to see over the past 20 years how communities have looked to Morgantown and the success they’ve had with the rail-trail and how it’s been the catalyst to open up that waterfront.”

Connecting trails and development

Belling, Spellman and Pack all denote the importance of community development around outdoor recreation. While West Virginia’s major economic focus is slowly shifting away from extractives like coal and natural gas to realizing its recreation potential, rail-trails will play a huge part.

And most of it comes down to the local economies with support from legislative leaders.

“One of the things we’ve seen, is we sell the concept of investing in trails to elected officials by selling them the short-term economic development – the dollars trail users leave behind when they buy stuff, spend the night, go to restaurants, buy beer, whatever it is,” Spellman said. “But that’s not what trails are about. That’s a part of it, we like to see that in our communities, but what it’s really about is those long-term economic benefits where you have a community people want to live in and bring their businesses to. The problem with that, when building trails, is that it’s a long-term process and elected officials are looking two-four years down the road at the next election. But it doesn’t work like that when you’re looking at those long-term, much more sustainable, important and impactful economic benefits that trails can bring.”

One also has to look at what the rail-trails cater to at the highest level. Unlike the Appalachian Trail or Pacific Crest Trail, and while they are multi-use trails for horse riding, hiking and biking, most of the longer trails are directed at one group: Thru bikers.

This is where Belling says the Mon River trail system, as well as P2P – should it be built – would benefit immensely.

“Bike tourism has increased tremendously,” Belling said. “So you’re primarily seeing cycling tourism happening, which is not what you’d see with the AT or PCT, and what’s happened is, that’s brought that kind of trail tourism to places and people who can now do it without setting aside [months of] their life. If you look at the Great Allegheny Passage, it’s getting millions of users that may do it in a week or two weeks, but potentially could do it in a few days.”

Still, there are hills to climb. To Belling, promotion and better community connections are needed moving into the future.

“We need to look at making better community connections so people in that community can have economic benefit connected to [the trail],” she said. “We’re lucky with the Mon River trail that it runs through a lot of downtown areas, but it doesn’t always [with other systems]. In many ways, the rail-trails have transformed life here in the Morgantown, turning the Monongahela River into a recreational and economic asset after years of neglect and abuse. Our communities have rediscovered their bikes, running shoes, rollerblades and dog leashes. The rail-trail has encouraged healthy, active lifestyles with trail users of all ages and abilities and seen a growing number of commuters to work and school, leaving their cars behind. There has been a rise of youth groups focused on running and biking such as Girls on the Run and several middle school bike clubs that make at least one long-distance rail-trail journey one of their goals.”

To Spellman and Pack, progress needs to be made on the literal connections.

“Last year, two years ago, we kicked off a project to connect a coast-to-coast rail-trail called the Great American Rail-Trail, and it’s really similar to the Appalachian Trail,” Pack said. “It’s something that’s been emerging over the years as more railroads are abandoned, in some ways, at least from the history I know of the AT, it was a coordinated effort to get those individual landowners along the way to give access through their property.

“In terms of thinking about economic development and the role trails can play in community building, a big part of the focus of our work the last 10 years or so has been looking at helping communities develop networks and systems. A single trail on its own can only do so much, and you have these incredibly trails like the GAP which has developed trail towns along its route and has done an amazing job of linking those communities into the trail. A lot of that is because it had really great trail support.”

Pack notes that the GAP model can be replicated in many places, but is most successful when everyone works together and is interconnected. This interconnectivity is something Spellman touched on and how P2P could connect West Virginia to Pittsburgh and Washington D.C. and everything in between.

“Keep in mind, if we can complete the Parkersburg-to-Pittsburgh Corridor, it will directly connect into the GAP,” Spellman said, “and all of a sudden we become another alternative for those long-term bikers. It will change everything in northern West Virginia as far as trail-use goes. The GAP is a great model, it’s a great economic development model. We can do that here, but we need to close some gaps.

What will benefit all communities, Spellman notes, is to build a trail that they love.

“Communities should build trails for themselves, not others,” he said, “and if they build a trail that they love and use, others will love and use that trail and want to move to that community.”

And for the trail in our backyard that we love so dearly? Well, it seems we’re on the right path.

TWEET @andrewspellman_