You wouldn’t guess it by just having a passing conversation with him, but Josh Compton is one of the most versed big game guides that has graced Alaska since 2007.

Compton, a resident of Harrisville, W.Va., lives a quiet life with his wife and son. He works for Dominion Energy all but two weeks out of the year when he makes his annual pilgrimage to Kodiak, Alaska. There he guides for Hunt Alaska Outfitters that’s owned and operated by an old colleague, Rick Hoskins.

“[Guiding in the Kodiak Mountains], that was my goal, I wanted to be a brown bear guide,” Compton said. “It worked out that I met Rick and I’ve been guiding for him since 2015.”

But to understand why Compton makes the 4,453-mile journey out of the bottom 48 to one of the most remote places on Earth, you’d have to know his roots.

Compton grew up in Cairo, a small town in Ritchie County that was one of the wealthiest areas during the early American oil boom. By the time Compton was growing up, though, Cairo had reverted to its rural roots with the biggest attraction being its old-style ice cream parlor. His grandfather and father introduced him to the outdoorsman life at a young age – as soon as he could walk, Compton recounted – and after graduating high school he attended Hocking Technical College in Nelsonville, Ohio, to add to his knowledge within the wildlife management program. There he took part in the ranger services program where he learned land navigation, wilderness survival, backpacking techniques and outdoor leadership skills. Unbeknownst to him, this would pay off later.

“As soon as I graduated a friend of mine offered me a job in road construction making a ton more money than I would have in any wildlife job. So I took that and didn’t use my degree for a long time. I thought, ‘You know I want to do something with my degree. It would be cool to be a hunting guide,’ ” Compton said.

He first began his search looking at outfitters in Colorado, but after a little bit of research, he ran into a slight problem.

“I wanted to be an elk hunting guide, but saw it dealt a lot with horses – I don’t know horses at all,” he said laughing.

The search continued.

“I started searching around on the internet – it’s a beautiful thing, the internet – and found a guide school in Alaska,” he said. “I called the guy up and told him I was interested, and he told me that they only took two people and were filled up, but [after] telling him about myself he told me with my credentials [from ranger services] I could go right into the Brooks Range and start an apprenticeship with an outfitter there for two years before I can guide.”

And from there, Compton made contact with Phil Byrd of Arctic North Guides. After some exchanges, Compton was on his way to Alaska to begin one of the biggest journeys of his life.

“I started green as grass – I didn’t even take a sleeping bag with me. Phil told me to bring my gun up and that I needed to kill a caribou for my apprenticeship, so I thought if it doesn’t work out at least I get a caribou on an Alaskan hunt,” Compton said laughing. “Long story short, I apprenticed with Bill and packed the meat out on hunts, cook and help set up camps. Then I started guiding for him for grizzly bear, caribou and a doll sheep.”

Once Compton was a licensed guide, he would spend 2-3 months in Alaska. He moved around to work for other outfitters: Ben Stevenson in the Talkeetna and Chugach Mountains in the southern portion of the state helping clients get grizzlies, moose and black bear, as well as mountain goats in the Chugach.

“There’s so much more to guiding than taking a guy out and getting him an animal,” he said, taking a short pause. “The first rule I was taught there was [to keep] my client alive.”

Danger is present in almost every hunting situation, but in the remote wilderness of Alaska, it’s easier for people to lose their lives. Compton recounted a story of his brush with death that happened in 2013.

“I was guiding on the Alaska Peninsula, and my client shot a brown bear. When I went down to retrieve the bear, it wasn’t dead yet and it charged me,” he said. “I shot the bear six times, the first one being from about 20 feet. Long story short, I killed it and it was a hairy situation. I thought to myself, I’m not going to tell my wife about this because it will freak her out. Then I got to thinking, if I don’t tell my wife, I can’t tell my buddies.”

It didn’t take long to get him off his scariest experience back onto his favorite ones.

Even though he’s successfully guided clients to harvest every Alaskan game animal excluding Muskox, Compton notes two hunts that have stuck with him over the years, both contenders for the best hunts of his life.

The first involved former State Delegate Jason Harshbarger (R-Ritchie) and four other friends from West Virginia. The group tackled a 21-day do-it-yourself hunt on and along the Yukon River. Each member of the hunting party killed a bull moose.

“You can use your imagination to [fill in] the rest,” Compton said. “We were on flat-bottom John boats on a river that was 3 miles wide cruising up there. It was a real hunt, catching fish and hunting.”

The other hunt involved a 65-year-old Chicagoan-turned-Alabaman named Ed on Fogneck Island.

“Sometimes I get clients – I don’t want to sound like an asshole or anything – but a lot of the people who have the money to go on those hunts are filthy rich. Most of them think, ‘Because I’m a millionaire, I know more than you,’ and that I’m working for them when I’m there to help them get an animal. I’m not their slave, I’m there to help them,” Compton said, prologuing the story. “But sometimes you get a gem – like a guy who’s saved up his entire life and enjoys the hunt [like Ed]. Ed had an accent mixed between Chicago and Alabama and was missing a big toe, but was full of heart and was happy to be there. He was totally in tune with me. We hunted for 12 days and had been unsuccessful because he was physically unable to get to the animals.”

Before Compton finishes his story, it should be noted that since 2007, Compton has only had three people not get an animal: One man had cancer, the other was 82-years-old and the third was subject to harsh weather.

“It was day 12, and I told him I really enjoyed the hunt but if he didn’t find a bear between 2 and 3 p.m. you won’t be physically able to get there and your hunt will be over. Sure enough, about 1 o’clock that day I found a bear on the hill. We started the [few hour] hike to get up there, and the bear was gone. I told him, ‘I don’t normally do this for safety reasons, but I’m going to blow a dying rabbit call.’ I started blowing the call, and there was nothing. I figured while we were up there I was going to take some scenery pictures, and just as I was putting my phone away I saw a fuzzball on top the hill about 400 yards out. The bear was coming to the call. I said, ‘Ed, get ready! The bear is going to come into us.’ It tried to hook around to our left to get our smell, so we moved on it, and then when we were going through a [patch of spruce] I happened to glance up and see the bear 50 yards away.

“Ed pulled up his gun and he made a perfect shot. The bear rolled down right in front of us, and he cried. That one there’s the top of the list.”

Although Compton loves guiding, his new favorite job is teaching his son how to hunt. Just 10 years old, his son is becoming a natural.

“He’s the little deer hunter,” Compton said. “He’s killed more big bucks than some adults. He killed his first buck when he was 7 and his first deer when he was 5.”

And whether its a product of breaking his son into the lifestyle of being an outdoorsman just as his dad and grandfather did when he was a youngster, Compton is beginning to notice how hunting is becoming more and more commercialized, something he sees as a detriment to the sport.

“It used to not matter what you hunted with, as long as you were out there hunting you were part of the family. Now, you’re not a hunter unless you shoot it with [something specific],” he said. “People get into the bickering and what they don’t realize is that they’re hurting everyone else by doing that. Say a new hunter comes into a Facebook group, shoots a 4-point buck and is so proud of it, posts in the group and you get some jack-nut who says, ‘Oh my gosh you should’ve let that go, it’s too small,’ well that’s his opinion. That’s what I think is going bad with the hunting world. Everyone thinks they’re a professional. It’s been humbling for me to go to Alaska and do these real things. These ‘professional hunters’ have no clue what it’s like to even be on a real hunt.”

Even then, he’s not going to let it ruin his experiences. He wants to continue to highlight the beauty of what hunting and fishing can be, whether it’s on private land in Ritchie County or the Alaskan bush as long as he’s physically able.

TWEET @ASpellman_DPost

Josh Compton poses with a bull moose he killed in Alaska. (Submitted Photo)

Small passenger planes are a common mode of transportation for Alaskan hunts in part to how remote Alaska is. (Submitted photo)

Josh Compton poses with a caribou. (Submitted photo)

Josh Compton packs out caribou antlers. (Submitted photo)

(Submitted photo)

Josh Compton and a client pose with a bear the client harvested. (Submitted photo)

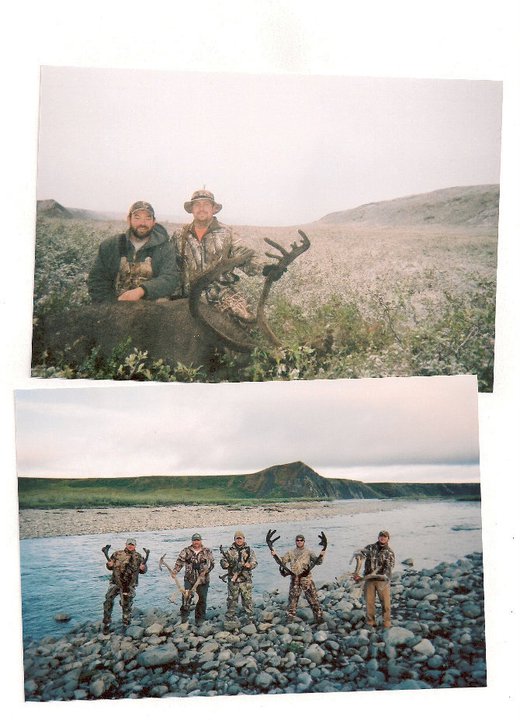

A photo collage of Josh Compton’s past hunts. (Submitted photo)

A photo collage of Josh Compton’s past hunts. (Submitted photo)