Friends of Deckers Creek has been working to clean up the creek since its formation in 1995. And it’s succeeding.

This is the first in an occasional series of stories to report on FODC’s Clean Creek Program: regular water testing and remediation efforts. This story offers an overview of the testing program.

Industrial activity along the creek in the early part of the 20th century filled it with waste and raw sewage. Mines dumped acid runoff into the creek.

“There are some sites where Deckers was completely dead and now we’re seeing fish come back,” FODC Executive Director Sarah Cayton said.

Cayton provided just a few numbers to illustrate the progress since FODC began consistent data collection under its CCP in 2002.

Average water quality in 2002: pH, 6.5 (acidic, on a scale of 0-14); iron, 1.77 milligrams per liter (mg/L); aluminum, 1.15 mg/L.

In 2019: pH, 7.53 (slightly base, 7 is neutral); iron, 0.44 mg/L; aluminum, 0.33 mg/L. The iron levels are about a quarter of what they were in 2002, the aluminum levels just between a quarter and a third of 2002.

The CEP test water quality quarterly at 13 sites from the headwaters in Preston County to just up from its mouth at the Mon River in Morgantown. The 13 stops take two days. The last was done in June; the next will be in September.

They test for such things as pH, conductivity (the water’s ability to conduct electricity, based on salinity; low conductivity is better), flow, iron, aluminum, magnesium, manganese and calcium.

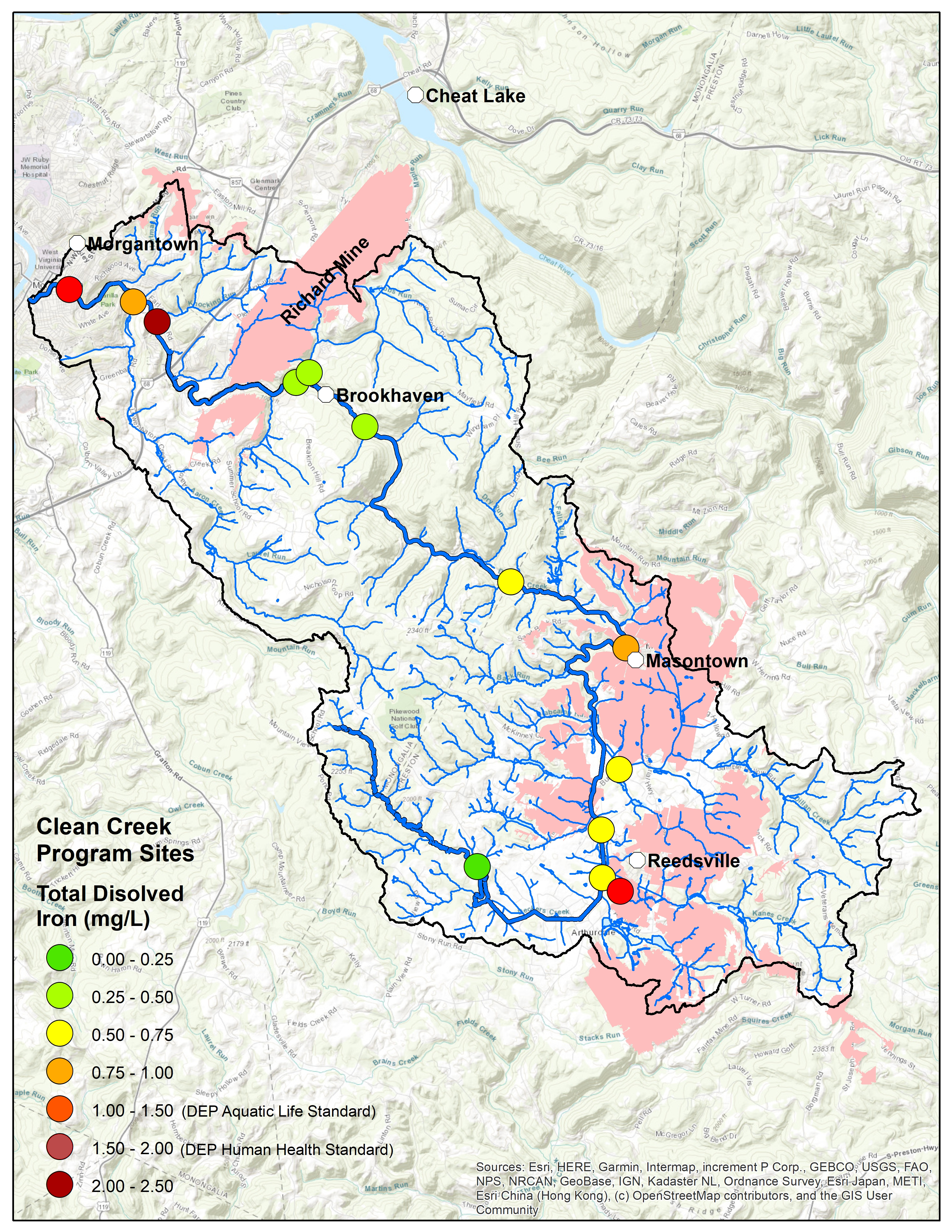

The map accompanying this story shows colored dots for average iron levels during the course of the CCP at the 13 testing sites, with green being low and red being high. You’ll se a red dot near Reedsville and an orange dot near Masontown below abandoned mines, which are shaded in pink.

At the top of the map, downstream from the Richard Mine, the dots are salmon, orange and red, indicating high iron levels from the acid mine drainage.

Annually, sometime in spring or summer, they test for macroinvertebrates – organisms without spines big enough to be seen with the naked eye. Particularly, they look for the levels of three “indicator species,” as prescribed by the West Virginia Stream Index from the Department of Environmental Protection: mayflies, caddisflies and stone flies.

They look for these bugs at riffles – shallow areas where the creek speeds over rocks and oxygenates the water. These are where these senstive bugs like to live and testing for their presence indicates which sites are improving, which are clean and livable and which still need work.

The presence of these bugs, Cayton said, is the best dictator of the water’s long-term health.

Also annually — late summer or fall – they sample for the presence of fish. There’s a strong public interest in the fish population, Cayton said, both for recreation and for the assurance the stream is healthy.

They stock the creek with brown and rainbow trout, Cayton said. The population isn’t self-sustaining yet, so they encourage catch and release fishing, but it’s not specified as a catch-and-release stream so some do take them for food.

They also sporadically test for metals, especially sampling around their treatment sites at some mine discharge points.

“Obviously acid mine draining is our biggest source of pollution in Deckers Creek,” Cayton said. “What’s important for people to know is we’re seeing a lot these great improvements.”

But people often ask why does FODC have to keep cleaning it and when is it going to be clean, she said.

She explained that treatment sites require constant maintenance and periodic replacement, and the mine drainage is perpetual, so the work is constant. “Things are working; it’s a circle all the time trying to keep up with the pollution.”

But the significant improvement in acid mine drainage levels has allowed FODC to expand its focus, Cayton said. Last year, FODC was one of 10 agencies to receive an EPA Environmental Justice Cooperative Problem Solving Grant.

They’re using the grant money to do 40 monthly tests around the entire watershed (outlined in black on the map) for e-coli and coliform bacteria. Their goal is to develop a swim guide that will be available via an app so people can track the day’s readings and know where it’s safe to swim.

The entire creek, Cayton said, is listed by the EPA as impaired for e-coli, but there’s been no real data on where or why. So this grant is helping them begin to understand what the problem is, where it is and, in the future, how to fix it.

Tweet David Beard @dbeardtdp Email dbeard@dominionpost.com

A brief history of Deckers Creek and FODC

The following is condensed from histories of the creek written by Billy Joe Peyton and Terry L. Falls.

Deckers Creek is named for the European family that settled at its mouth in the spring of 1758. Thomas Decker was the first to settle in the area of Deckers Creek and the Monongahela River that year. He was joined by his brothers Tobias, Garrett, and John Decker and their families, and some others.

Early on, industries used the creek for water power for a forge and iron furnace, grist mills, saw mills, and a pottery and a paper mill.

In 1886 the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad reached Morgantown along the Monongahela River. Industrialist George Sturgiss led the effort in 1899 to build the Morgantown and Kingwood Railroad up Deckers Creek. The line reached Masontown by 1902, opening the area’s reserves of timber, coal, and limestone for harvest.

Mines, quarries, and coke ovens soon filled the Deckers Creek valley from Reedsville to Rock Forge. In 1903 a tin plate mill opened in Sabraton and a large modern electric plant was built along the creek in Morgantown.

But the rapid industrialization took its toll. Water quality declined and aquatic life diminished. Recreational fishing and boating on the creek ceased after acid mine runoff and open sewage fouled the water.

By 1935, state officials warned Morgantown to clear the stream of sanitary waste. In the late 1930s Morgantown realized it needed an interceptor sewer along Deckers Creek but for lack of money the sewer wasn’t completed until 1962.

This eliminated sewer odors but mine acid and raw sewage still entered the watershed from points upstream.

Then in 1995, a group of kayakers, rock climbers and other creek lovers formed Friends of Deckers Creek and started organizing clean-ups of illegal dumps and monitoring water quality.

By 1997, the group began receiving small grants to support its work. It obtained nonprofit status in 2000 and held its first membership drive in 2001.

In 1998, the state Department of Environmental Protection and federal Natural Resources Conservation Service committed $10 million to clean up acid mine drainage in the Deckers Creek watershed, an effort that continues to be guided by FODC even now.