FAIRMONT — West Virginia’s first orbiting satellite — the STF-1 CubeSat — marked its 145th day in space on Friday.

And the pioneering simulation software that is keeping it up there in pristine working condition — called NOS3 — has been nominated of NASA’s prestigious 2019 Software of the Year award.

And the pioneering simulation software that is keeping it up there in pristine working condition — called NOS3 — has been nominated of NASA’s prestigious 2019 Software of the Year award.

STF-1 — Simulation to Flight 1 — is busy gathering data for four WVU research projects, and snapping pictures for publicity and general awe-inspiration,

But the real significance, said Mattt Grubb, lead engineer for STF-1, and Scott Zemerick, chief systems engineer for Fairmont-based TMC Technologies, is that NOS3 works and can serve small-statellite developers across the country and the world.

But the real significance, said Mattt Grubb, lead engineer for STF-1, and Scott Zemerick, chief systems engineer for Fairmont-based TMC Technologies, is that NOS3 works and can serve small-statellite developers across the country and the world.

NOS3, — NASA Operational Simulator for Small Satellites — is open source, which means anyone can download it for free and use it on a laptop – to prepare a satellite for orbit or just learn about them.

“The NOS3,” Grugg said, “that software, since it’s been open sourced, has been utilized by a lot of other people: the Air Force, government agencies, universities as well. It’s already been proven. We’ve proven it in orbit, now. We’ve launched a spacecraft and we can say without a doubt it has increased our reliability and definitely reduced our cost. And our mission timeline was actually much quicker than it would have been if we didn’t have a simulation platform to test all the stuff with.

“The NOS3,” Grugg said, “that software, since it’s been open sourced, has been utilized by a lot of other people: the Air Force, government agencies, universities as well. It’s already been proven. We’ve proven it in orbit, now. We’ve launched a spacecraft and we can say without a doubt it has increased our reliability and definitely reduced our cost. And our mission timeline was actually much quicker than it would have been if we didn’t have a simulation platform to test all the stuff with.

“We do have zero software issues, and that’s a very rare thing, especially in a small sat,” he said.

Zemerick added, “It’s unheard of sometimes. A lot of times, they’re so inexpensive to build, they go up there and they disappear.” The developers lose contact with them almost immediately and no one knows what happened.

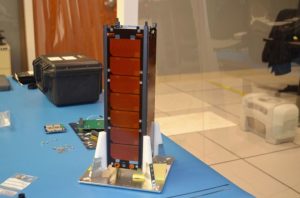

Small satellite means very small: 10 by 10 by 34 centimeters (about 4 by 4 by 13.5 inches). STF-1 is called a CubeSat because it’s three 10×10 cm cubes linked together into a standardized satellite that can be mounted on a rocket to go into orbit. The rocket will take up a cluster of them and scatter them along its path.

STF-1 circles the Earth every 96 minutes, 500 kilometers up, above the orbit of the International Space Station.

STF-1 got its start back in 2014, when the West Virginia Space Grant Consortium approached WVU and NASA’s Fairmont IV&V (Independent Verification and Validation; the center is now named for former NASA mathematician Katherine Johnson) center to put together a team.

NASA selected the project in 2015 for its CubeSat Launch Initiative. TMC is the lead contractor for IV&V’s JSTAR lab, which creates hardware-simulation software through its NOS engine.

JSTAR generally does simulations of big spacecraft, Zemerick and Grubb said, said, to reduce risk and increase reliability of systems.

“The idea for this mission was to take what we do in our day job and roll it into a small satellite, a CubeSat,” Grubb said. “We took the simulation technology that we’ve used for all our different missions and tailored it to the small sat world.”

The outside of the satellite is covered with solar panels. A backup chassis at JSTAR just has the copper-colored plates where the expensive panels would be mounted. At the top is a package of four antennae to gather data.

WVU provided the team with four payloads of computer cards to place inside the tiny satellite. “Our goal was to prove the simulator, but we also wanted to support their goals,” Grubb said.

One package, from WVU Physics and Astronomy, studies space weather: radiation, solar flares, charged particles plasma. One from the Lane Department of Computer Science and Electrical Engineering tests radiation-proof LEDs and photodiodes to use for distance measurement and shape rendering. The other two, both from WVU Mechanical and Aerospace Engineering, test different means of precise orbit determination.

Also inside are the flight computer and the camera.

The unit was tested in April 2017. In April 2018, Grubb took it California to ready it for launch. From there, STF-1 went to New Zealand and launched on Dec. 16.

Then came the longest wait. At least, it felt like it: a nail biting three days before they were able to contact it and talk to it.

“That was the most grueling three days, I think, of all,” he said. “That was a great day. That was when we knew we were alive and that we’d done something right.”

They did some more checks as it orbited and on Feb. 12 this year they began the experiments. They talk to it once or twice a day from the operations center: an ordinary desktop computer and 20-inch screen on a table inside a room with some other computers and a couple big screens in the IV&V office.

They estimate the $185,000 STF-1 will orbit for about 16 years. The mission was complete after three months. Now they’re in an extended period gather more data to feed to WVU researchers — a draw for grad students — and keep taking pictures.

Grubb is thrilled with a recent picture of sunrise over West Virginia. It shows the curve of the Earth across the top, the bright ball of the sun off to the right and an antenna projecting across the middle. It looks good on a giant screen but wouldn’t reproduce well on a newspaper page.

They’re also using the extended time to train more operators. Originally there were just two, Grubb said. Now they’re up to five.

They run STF-1 in space in tandem with the NOS3 software in Fairmont. The program, in essence, thinks it’s in space. Should an error ever occur in space, they can simulate it exactly in the office and figure out the cause and the solution.

Because NOS3 is open source and generic, any user can tailor it to suit their particular CubeSat, Zemerick said. The goal of the simulator is to make sure it works in space before it launches. “There’s no go-backs, there’s no fixing it. It has to work the first time.”

Along with monitoring STF-1 Daily, they’re waiting to hear about the NASA’s software award winners. NOS3 was nominated by the Goddard Space Flight Center.

The prize, from NASA’s Inventions and Contributions Board recognizes NASA-developed software that has significantly enhanced the Agency’s performance of its mission and helped American industry maintain its world-class technology status. It must be “creative, usable, and transferable, and possess inherent quality.”

The top prize is $100,000, but that’s less important than the recognition and the success, they said.

“It’s hard to win,” Zemerick said, as it’s competing with software all across NASA.

They’ve proved it works, Grubb said, and that it’s usable and transferable. “If we can polish it with a Software of the Year, I would say that’s the icing on the cake.

TMC President and CEO Wade Linger is hoping the success of STF-1 will lead to getting the chance to build more spacecraft in West Virginia.

“TMC is always looking for creative ways to commercialize the work we do for our valued government customers,” he said. “We can duplicate the success of the STF-1 project and build similar CubeSats right here.”

Tweet David Beard @dbeardtdp Email dbeard@dominionpost.com